In one of the most remote and inhospitable places on earth, Peter Hammarstedt had found company.

But it wasn't the sort of company he was accustomed to keeping. Metres away, in a desolate patch of Antarctic sea called the Banzare bank, one of the world's most notorious pirates was engaged in an act of plunder.

The pirate was not a person, but a ship, a 62m fishing vessel named Thunder. Banned from fishing in the Antarctic eight years earlier, the Thunder had since been on a crime spree that had netted her owners more than $60 million from illegal catches, as well as first place on Interpol's Purple Notice List of most wanted poachers.

The Thunder's prey of choice was toothfish, often known as white gold in the trade on account of the high prices it can fetch.

Until this encounter at the bottom of the planet in December 2014, the fugitive ship had proven adept at evading justice.

And it wasn't about to yield on this occasion. Instead of responding to radio calls from Hammarstedt's vessel to cease and desist, the Thunder opened her throttles and fled.

Almost four decades earlier, Lee Lantz, an American seafood merchant was on the hunt for new species of fish to market back home.

At a fishing port in Chile he found what he was looking for: a fish with buttery white flesh and a mild, non-fishy flavour. One that was incredibly versatile and hard to overcook.

Lantz had tasted his first Patagonian toothfish, a human-sized deep-living fish found only in the planet's coldest waters. But he knew that the toothfish's ugly appearance and even uglier name would make it a tough sell, so he invented a more appealing moniker: Chilean sea bass.

The rebrand was a success, and it wasn't long before his creation was gracing the tables of upscale seafood restaurants around the world.

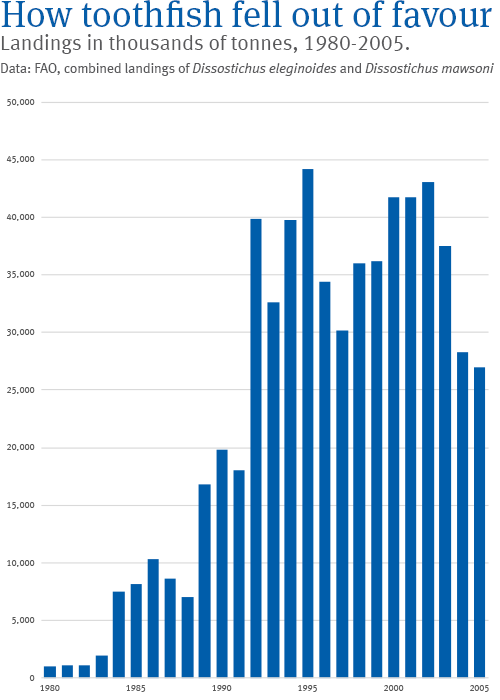

With demand and prices surging, the white gold rush began in earnest.

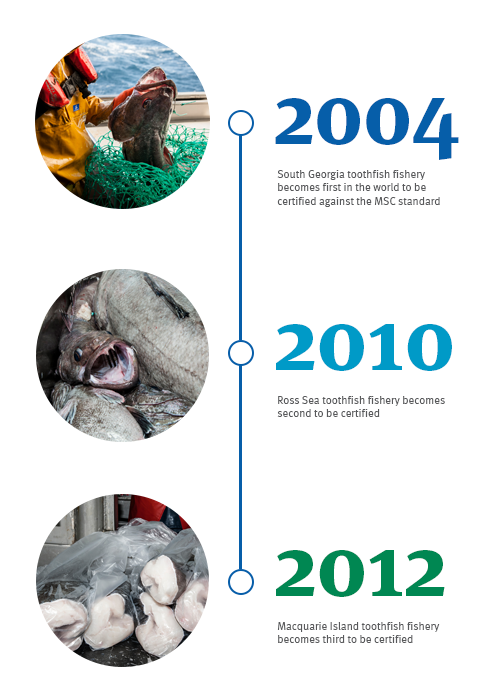

Formed in 2003, COLTO works to eliminate illegal fishing for toothfish and to promote sustainable toothfish fisheries.

Martin Exel, its former chair, puts the coalition's success in achieving these aims down to its cooperative nature.

"You can't underestimate the importance of collaboration between governments, retailers, scientists and (otherwise rival) fisheries. Although we compete in the marketplace, there's strong recognition that we need to work together as an industry on the water to overcome bigger issues."

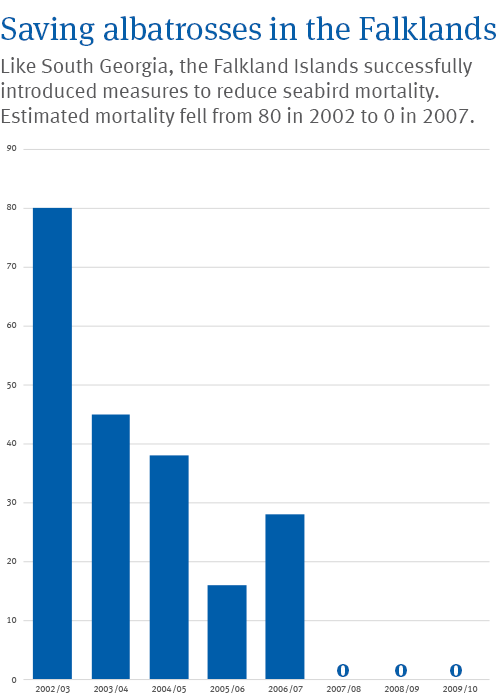

Not all of those bigger issues are centred on illegal fishing. At the time of COLTO's founding, there was concern that the way in which toothfish were caught was endangering the future of seabirds like albatrosses and petrels. The bait the fishery used on its longlines was often frozen, and since ice floats, it would stay on the surface until thawed.

When birds tried to eat the frozen morsels, they would often become hooked, and get dragged below the surface as the line sank. So large was the issue that around 100,000 albatrosses were being killed each year, threatening previously healthy populations.

Their plight even attracted the attention of Prince Charles, who wrote to the UK's then environment minister, Elliot Morley, saying:

"I particularly hope that the illegal fishing of the Patagonian toothfish will be high on your list of priorities because, until that trade is stopped, there is little hope for the poor old albatross".

A few months after the Falklands fishery was certified, and a fortnight after the Atlas Cove had briefly joined the chase, it was all over.

The Thunder met its end in the seas off Sao Tome and Principe, close to where the equator and the prime meridian meet. All hands were rescued, but while the captain may not have gone down with his ship, the prospects of the pirates did.

With organisations willing to go to the very ends of the earth to protect the toothfish, the risks no longer outweighed the rewards. Today, none of the so-called "bandit 6" of pirate vessels remain active. Indonesian authorities blew up the last, the Nigerian-flagged Viking, in March 2016.

With illegal fishing at its lowest recorded level and seabird mortality virtually eliminated, consumers are warming to toothfish once more.

The MSC's Chain of Custody Standard has been instrumental in this transformation. Through the use of secure at-sea labelling, supply chain monitoring and DNA testing, the Standard has helped restore consumer confidence in toothfish by ensuring that dinner plates are free from illegal catch.

Partly as a result, in the last year alone, the wholesale price of toothfish in the US has skyrocketed from $6-$33, an increase of 450%.

Thanks to improved management, smarter practices and certification, toothfish is back on the menu.